Jo Bentdal’s art project consists of a total of 12 photographs from the series The Law of the Instrument and Common Sensibility.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

Photo documentation: Jon Gorospe

Jo Bentdal’s art project consists of a total of 12 photographs from the series The Law of the Instrument and Common Sensibility.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

Photo documentation: Jon Gorospe

In both images and text, the art project engages with the audience and encourages contemplating the individual and society – a subject matter achieving new relevance in public space.

The curious and colorful photographs, currently at display in Munkedamsveien, blown up to 2 x 3 meters, are highly prominent for everyone passing by, either encountering the images up close or experiencing them from afar. In Dokkveien, the portraits of the girls, 12-15 years of age, sit as if rendered in a renaissance oil painting, gazing towards the National Museum.

The art project is produced in collaboration with Kulturbyrået Mesén, art consultant and art producer.

The descriptions below of the artworks are by the artist.

The portraits in Common Sensibility represent a generation of girls on the threshold of adulthood, casually dressed in their everyday attire, but instructed into a ceremonious and formal pose.

Tension can be sensed as the images emanate both strength and vulnerability, suggesting the sitter’s inner psychology or state of mind. Are the parameters set by tradition and previous generations acceptable? The artistic measures that are applied in these pictures support the impression of authority and entitlement in the new generation, but they also represent a confinement to their nature, a source of limitation and unease. In the confrontation with observers, can they trust us?

The project is, among other things, investigating the nature of power structures in society: the individual versus the collective, formal versus natural authority, and tradition versus innovation.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

Why the title Common Sensibility?

As a background, Bentdal recommends we relate to the thoughts of Immanuel Kant, Hannah Arendt, and perhaps also Jean-François Lyotard on the subject “sensus communis”. Replacing “sense” with “sensibility”, he wants to introduce a developed version of the term common sense, a version more aligned with the intuitive, analytical, and spiritual synthesis he suggests art – and cerebral life in general – could and should be.

Although the format and mode might reflect social structures and the constraint of conformity, the photographs also demonstrate that in restrictions there are possibilities. Through the push and pull of individual characteristics and strict posture, subtle hints of the girls’ personality are revealed/expressed. The repetition of stance and structure signalize past pictorial traditions, all the way back to the first psychological portraits of the renaissance, simultaneously redirecting our attention towards present-day culture and norm.

In the long term, the generations to come will inherit and live with the results of our endeavors, and so, we all ultimately report to them.

The full series consists of a total of 11 portraits.

“Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.” Abraham Kaplan, 1962.

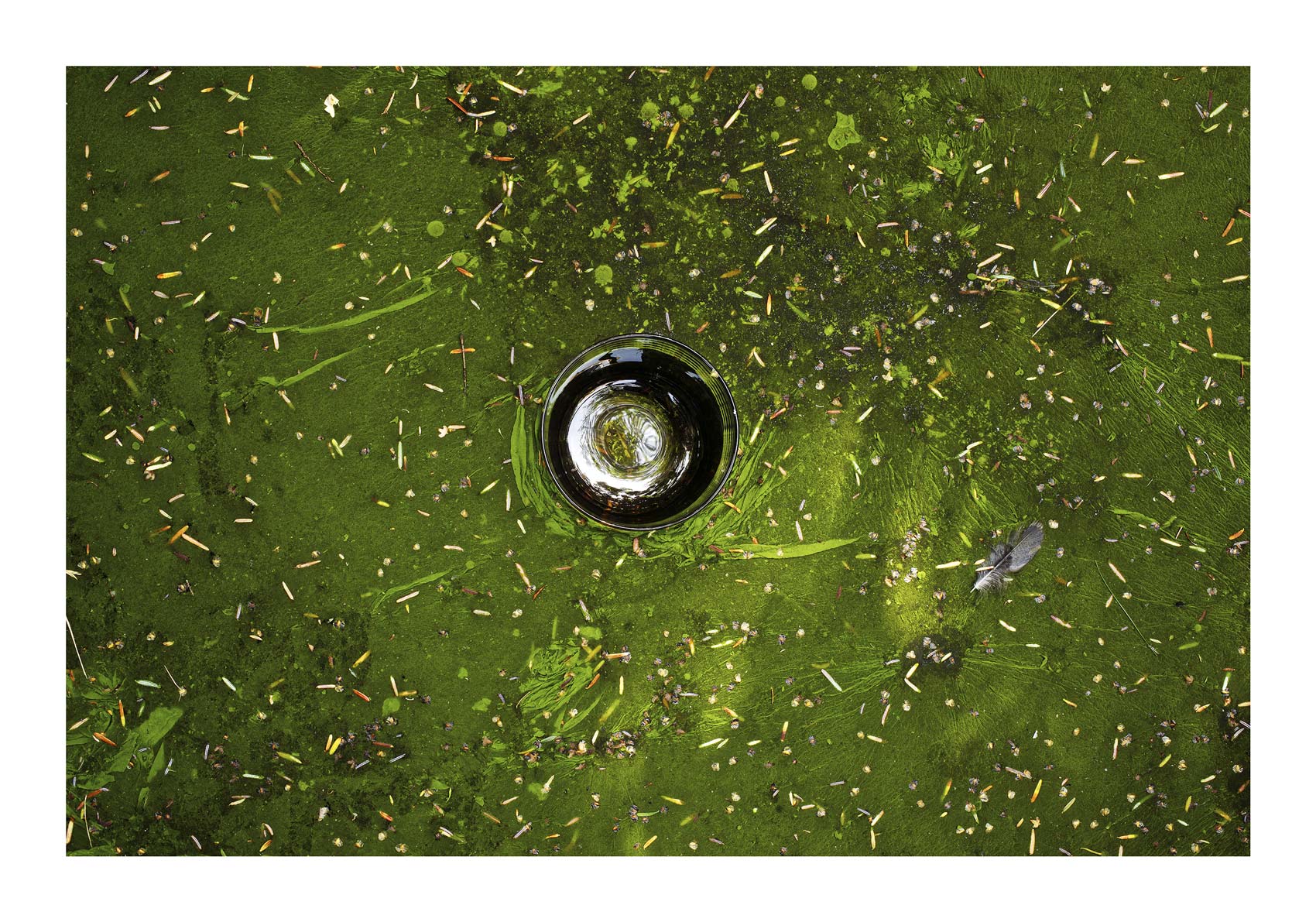

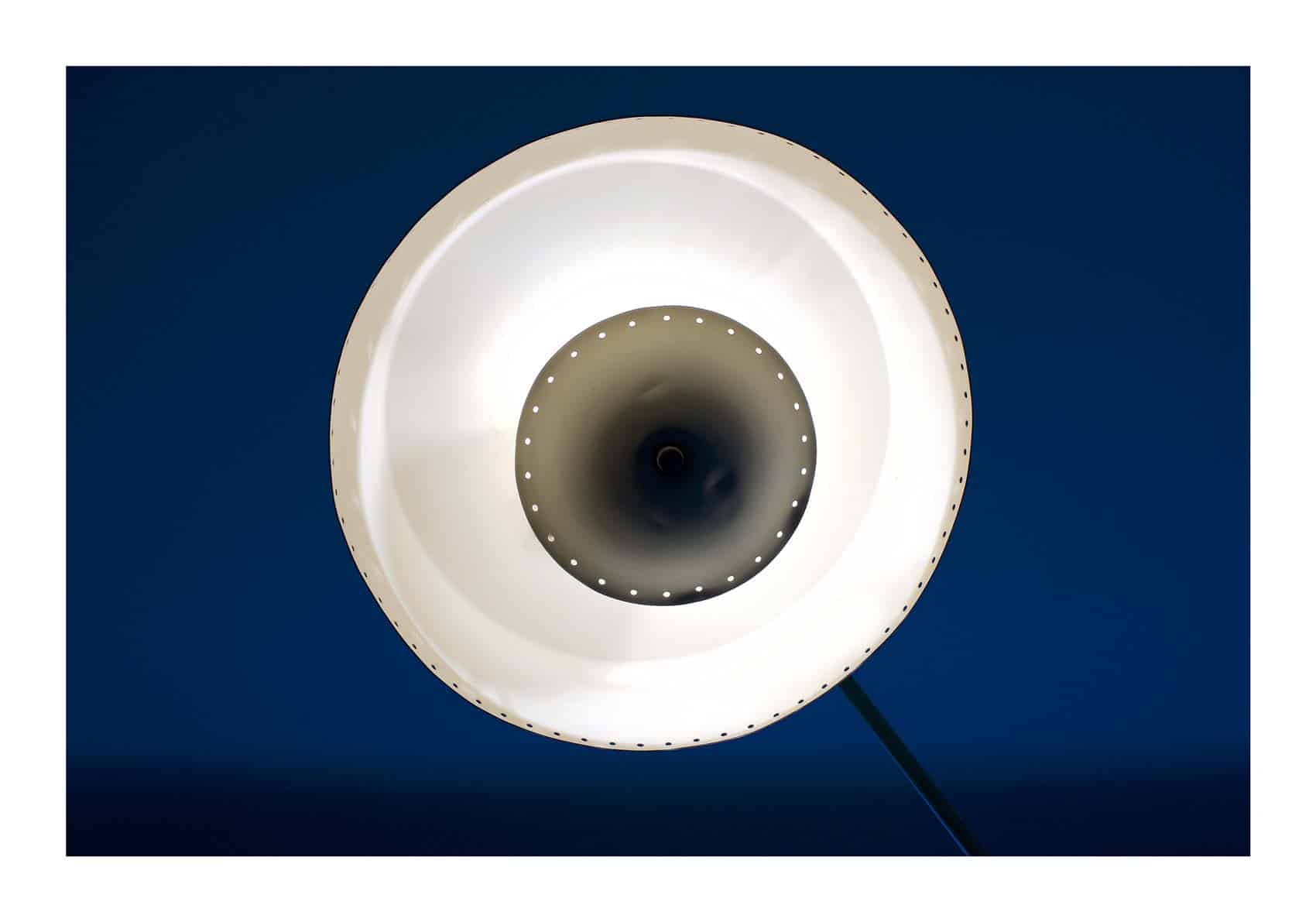

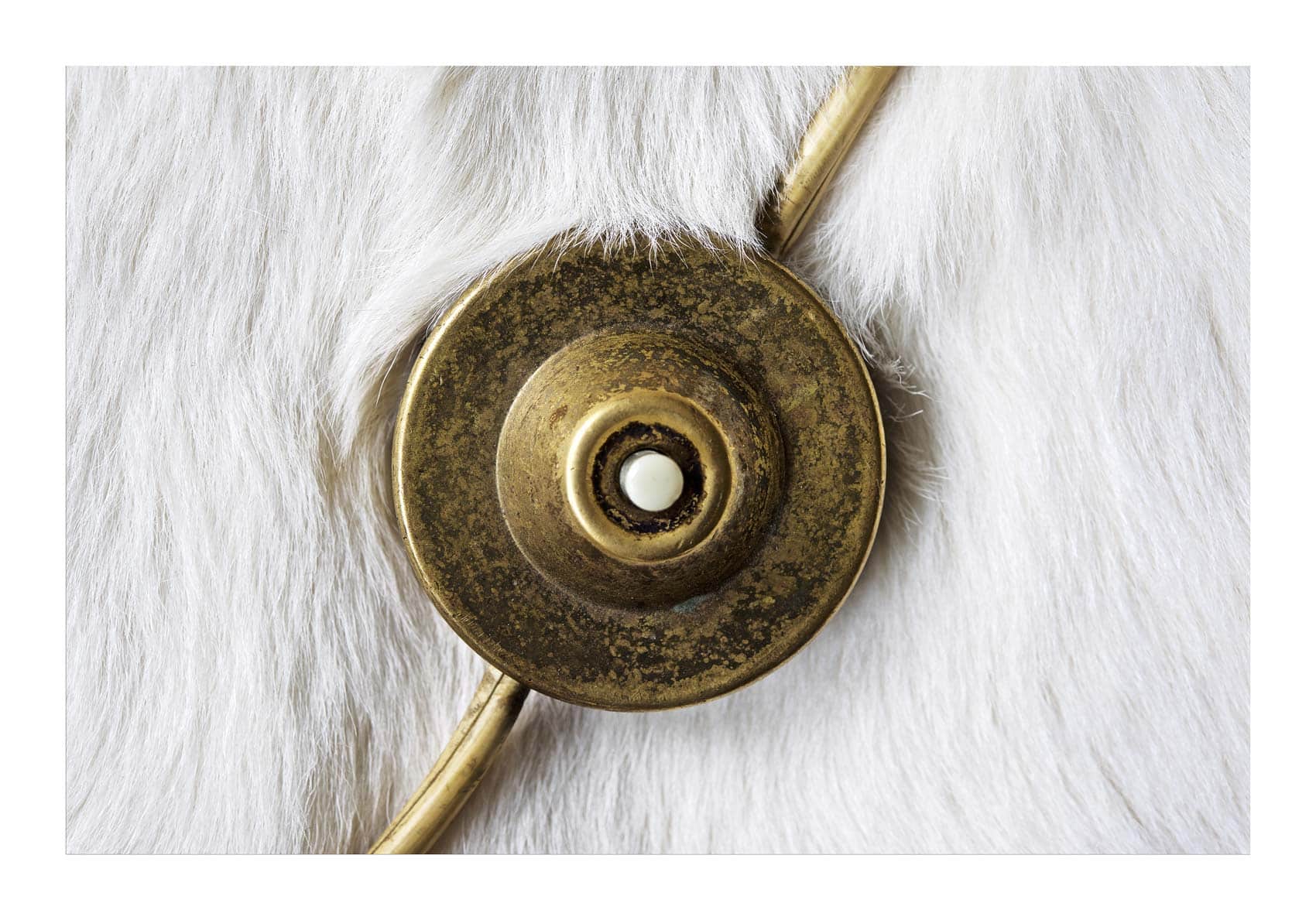

Jo Bentdal’s photographs turn everyday objects into shape, light, and color. But what do we see? A hammer that floats? A jack hovering in empty space? The images are colorful and seductive, yet fairly hard to read. They invite meta-cognition: should we understand the images, or just feel them?

The Law of the Instrument explores the notion that we humans as a species hold a powerful tool that has ensured our dominance on the planet: our analytical brain. Close to 100,000 years back, spoken language entered the stage. 10,000 years ago we began cultivating land, cities emerged, and we developed the written language. 75 years ago, digital data processing arose. The trajectory seems to have been exponential since the word, and AI and the Technological Singularity is merely a prophesied culmination of the graph.

Yet, we are only human and our perspective is anthropocentric, and AI, with all its promises and perils, represents an even more narrow vision of life on earth.

Maybe the time has come to stop considering our main strength as something unconditionally positive, but still hope we have the ability to limit our negative impact on life on earth?

Artist: Jo Bentdal

«The law of the instrument» is a cognitive bias that involves an over-reliance on a familiar tool. As Abraham Maslow said in 1966, «I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it was a nail.»

Is our rational brain the Maslowian hammer of humankind? Will it float?

Artist: Jo Bentdal

Our perception of the world is brought to us through our five senses. The senses are evolutionary products of the environment on planet earth. If our ears were any more sensitive, we would hear a constant humming caused by the brownian motion of the molecules of the air surrounding us. Our eyes are adapted to the exact wavelengths that dominate the emission from the sun after filtering through the earth’s atmosphere, and if three photons or more reach our retina, a signal is sent to our brain. Our physical senses are tightly linked to the «real world» around us, but what we perceive as reality is really just our brains’ processing of the signals from the outside «real world».

When constructing our worldview, we depend on this input, and when it comes to direct and focused observation of tangible elements in our close surroundings, the rigid laws of nature and a robust process of evolution have seen to it that our perception is fairly reliable. But when we start abstracting, we have to rely on our own approximations, models, theories, and generalizations. These are structures we have constructed ourselves in our neocortex, and there is really no guarantee that our perception in any given context is an objective and robust representation of reality, nor does it fully ensure a well-functioning approach to a given situation.

Hence, all of our thought processes that amount to more than mere instincts, must have a degree of fluidity and adaptability. They need to be context sensitive. They need to be broken down and corrected when they don’t serve their purpose!

Artist: Jo Bentdal

When did information transcend into language, and language into global communication?

Will we, or some future artificial intelligence (AI) entity, soon mount a Babel 2.0? Is the technological singularity*, expected by some to arrive in 2040–50, the point where technology escapes nature or are we already here to cause that disruption?

300,000 years old fossils of Homo sapiens, along with stone tools, were found in Morocco in 2017. There is no consensus on the origin or age of human language but Noam Chomsky, a prominent proponent of discontinuity theory, argues that a single chance mutation occurred in one individual around 100,000 years ago, installing the language faculty (in the mind-brain) in «perfect» or «near perfect» form. A majority of linguistic scholars, as of 2017, hold continuity-based theories, but there are indications of early language 100,000 years ago.

8–10,000 years ago, we started farming the land, formed cities, and we started writing. 75 years ago we invented digital computing (1941).

Hence, the technological singularity*, expected by some to occur around 2040–50 (when AI «goes through the roof»), really seems to be no more an extension of a «biological singularity*» that is already present on earth in the form of the human brain. Our cultural, informational, and technological trajectory seems to have been exponential for at least 100,000 years and is currently wreaking havoc on the planet.

* a singularity, simply (and thus precisely) put, is a point where a development goes towards infinity and hence is perceived from the surroundings to change instantaneously.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

In the world of human communication and information, everything is an abstraction.

It is fair to suggest that our descriptions of the laws of nature, described in physics, are about as objective as they get. But even they are theories and approximations to objective reality.

Since the Age of Enlightenment, the effectiveness of the methodology of natural sciences in developing functioning technologies has led us to where we are now: prolific and comfortable, and at the brink of destroying the planet. It has also inspired most modern human endeavors to apply a similar methodology and confide in popular theories. But most other fields operate with parameters that are much less stable, measurable, and repeatable (and hence confirmable) than those of the natural sciences.

Adding to that mess, we tend to form «intellectually inbred tribes» that reconfirm consensus based on well-established biases without much incentive for correction from other disciplines or «tribes» with other vantage points.

The sum total of all our endeavors has, however, reached a level of impact that makes it measurable on a planetary scale. There’s overwhelming evidence, measurable on a number of parameters, that we as a species are on an unsustainable path. This should force us to realize we have a collective interest and responsibility to set things straight. And just some more of what human beings have done so far, will surely not do the trick.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

We are only human and have a hard time seeing things from any other perspective than that of a human being. The sum of all human knowledge will always be a very limited part of the total picture.

What we think we know as individuals will never amount to more than a fraction of the total human knowledge, and it will always be subjective and biased.

This leaves us with having to

and try to understand and limit our negative impact on our surroundings.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

Our tool-making, and subsequent technological development, is a product of our natural evolution and hence a part of nature. It has, anyhow, reached a point where it alters our surrounding nature on a global scale in many ways that are not so great. There is no guarantee against evolving into extinction. Other species are already going extinct at a record pace as a result of our actions. Factors critical to the living conditions of human beings are also showing clear signs of threat to our own well-being.

The planet, however, will survive. On planet earth, there is a vast amount of time left for new species to evolve far beyond our current level of sophistication, with or without our own genes as contributing factors. It seems to me that a reasonable objective includes trying to give the best parts of our cultural heritage a chance to live on and evolve further. We should also try to avoid unnecessary setbacks (which presupposes that we stop doing a number of stupid things we are currently proudly putting a lot of effort into doing). Furthermore, we should aim to sustain other products of evolution as well as our own genes as it would (among other reasons) limit our own suffering.

There is simply no viable way to beat nature.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

«Where is everybody?» The Fermi paradox, named after physicist Enrico Fermi, is the apparent contradiction between the lack of evidence and the high probability estimates for the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations.

One way of explaining the absence of evidence of any intelligent life other than ourselves, is that there must be a very small likelihood for advanced life forms to evolve to a level where traces of their existence can be trailed by us. Either there’s a barrier in the evolution of intelligent life that makes us one of very few instances of civilizations with technology. There must be a barrier we somehow have passed in our past, despite the odds. Or there is a barrier in our future that makes it very unlikely for a civilization with technology to develop to a level where it ventures out into the universe, or even emits traceable signals (electro-magnetical or other). The latter can indicate a high likelihood of rapid collapse of technologically advanced civilizations. This theory is called «The Great Filter».

Anyhow, maybe there’s simply no real sense in hurrying to colonize the universe? Maybe the only sensible thing to do is to ensure responsible handling of life on earth? We are, as mentioned, finely tuned to life on this planet, and it to us. The promise of an exciting future among the stars is like the captain of the Titanic announcing that the real party is starting later – in the lifeboats.

Artist: Jo Bentdal

How come we find ourselves in an extremely fine-tuned and hence stable universe (this appears to be an almost miraculous coincidence if we look at the cosmological prerequisites, unless we allow a multiverse or megaverse speculation), and on a planet so well suited for supporting our existence as well as that of all other life forms on earth? The anthropic principle states that we would simply not be here to ask the question if this was not the case!

Human ambition to expand our reach has led to a number of inventions and designs, one of which, albeit hypothetical, is the Dyson sphere. This is the idea of a megastructure that completely encompasses a star to capture a substantial part of its energy output.

A relevant question is whether we as a species might already be in the process of sucking up all potential for life in our solar system, and whether that is a good thing or not?

Artist: Jo Bentdal

You might merely be a brain floating in empty space, and all your memories, perceptions of “reality”, and expectations for the future might exist but in this lonely brain?

Entropy calculations, first done by philosopher and physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906), indicate that the scenario above might be more likely than the formation of an actual universe based on established cosmological theories.

I, for one, choose to believe that there is more to the picture than this single brain (again, a megaverse/multiverse speculation could support that belief), and that the “reality” is real. In the words of one of the fathers of string theory, Leonard Susskind: “It all adds up to normality.”

Jo Bentdal (b. 1968) is a visual artist holding an MSc in applied physics. He has a background of 16 years as a strategy consultant, focusing on digital technologies and communication before turning to full time art photography in 2010. His debut was at the annual national art exhibition ”Høstutstillingen” in Oslo in 2015.

Purchased by Strays Foundation, the DNB art collection, Kunst i skolen, Tusen Takk Foundation (USA), The Møller Collection, Ferd, as well as private collectors.

Selected Exhibitions:

* juried exhibitions